Arrays

by Casey Reas and Ben Fry

This tutorial is the Arrays chapter from Processing: A Programming Handbook for Visual Designers and Artists, Second Edition, published by MIT Press. © 2014 MIT Press. If you see any errors or have comments, please let us know.

The term array refers to a structured grouping or an imposing number: “The dinner buffet offers an array of choices,” “The city of Boston faces an array of problems.” In computer programming, an array is a set of data elements stored under the same name. Arrays can be created to hold any type of data, and each element can be individually assigned and read. There can be arrays of numbers, characters, sentences, boolean values, and so on. Arrays might store vertex data for complex shapes, recent keystrokes from the keyboard, or data read from a file. For instance, an array can store five integers (1919, 1940, 1975, 1976, 1990), the years to date that the Cincinnati Reds won the World Series, rather than defining five separate variables. Let's call this array “dates” and store the values in sequence:

Array elements are numbered starting with zero, which may seem confusing at first but is an important detail for many programming languages. The first element is at position [0], the second is at [1], and so on. The position of each element is determined by its offset from the start of the array. The first element is at position [0] because it has no offset; the second element is at position [1] because it is offset one place from the beginning. The last position in the array is calculated by subtracting 1 from the array length. In this example, the last element is at position [4] because there are five elements in the array.

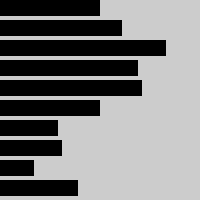

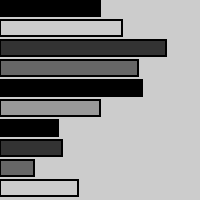

Arrays can make the task of programming much easier. While it's not necessary to use them, they can be valuable structures for managing data. Let's begin with a set of data points to construct a bar chart.

The following examples to draw this chart demonstrates some of the benefits of using arrays, like avoiding the cumbersome chore of storing data points in individual variables. Because the chart has ten data points, inputting this data into a program requires either creating 10 variables or using one array. The code on the left demonstrates using separate variables. The code on the right shows how the data elements can be logically grouped together in an array.

int x0 = 50; int[] x = { 50, 61, 83, 69, 71,

int x1 = 61; 50, 29, 31, 17, 39 };

int x2 = 83;

int x3 = 69;

int x4 = 71;

int x5 = 50;

int x6 = 29;

int x7 = 31;

int x8 = 17;

int x9 = 39;

Using what we know about drawing without arrays, ten variables are needed to store the data; each variable is used to draw a single rectangle. This is tedious:

int x0 = 50;

int x1 = 61;

int x2 = 83;

int x3 = 69;

int x4 = 71;

int x5 = 50;

int x6 = 29;

int x7 = 31;

int x8 = 17;

int x9 = 39;

fill(0);

rect(0, 0, x0, 8);

rect(0, 10, x1, 8);

rect(0, 20, x2, 8);

rect(0, 30, x3, 8);

rect(0, 40, x4, 8);

rect(0, 50, x5, 8);

rect(0, 60, x6, 8);

rect(0, 70, x7, 8);

rect(0, 80, x8, 8);

rect(0, 90, x9, 8);

In contrast, the following example shows how to use an array within a program. The data for each bar is accessed in sequence with a for loop. The syntax and usage of arrays is discussed in more detail in the following pages.

int[] x = {

50, 61, 83, 69, 71, 50, 29, 31, 17, 39

};

fill(0);

// Read one array element each time through the for loop

for (int i = 0; i < x.length; i++) {

rect(0, i*10, x[i], 8);

}

Define an Array

Arrays are declared similarly to other data types, but they are distinguished with brackets, [ and ]. When an array is declared, the type of data it stores must be specified. (Each array can store only one type of data.) After the array is declared, it must be created with the keyword new, just like working with objects. This additional step allocates space in the computer's memory to store the array's data. After the array is created, the values can be assigned. There are different ways to declare, create, and assign arrays. In the following examples that explain these differences, an array with five elements is created and filled with the values 19, 40, 75, 76, and 90. Note the different way each technique for creating and assigning elements of the array relates to setup().

int[] data; // Declare

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

data = new int[5]; // Create

data[0] = 19; // Assign

data[1] = 40;

data[2] = 75;

data[3] = 76;

data[4] = 90;

}

int[] data = new int[5]; // Declare, create

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

data[0] = 19; // Assign

data[1] = 40;

data[2] = 75;

data[3] = 76;

data[4] = 90;

}

int[] data = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 }; // Declare, create, assign

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

}

Although each of the three previous examples defines an array in a different way, they are all equivalent. They show the flexibility allowed in defining the array data. Sometimes, all the data a program will use is known at the start and can be assigned immediately. At other times, the data is generated while the code runs. Each sketch can be approached differently using these techniques.

Arrays can also be used in programs that don't include a setup() and draw(), but the three steps to declare, create, and assign are needed. If arrays are not used with these functions, they can be created and assigned in the ways shown in the following examples.

int[] data; // Declare

data = new int[5]; // Create

data[0] = 19; // Assign

data[1] = 40;

data[2] = 75;

data[3] = 76;

data[4] = 90;

int[] data = new int[5]; // Declare, create

data[0] = 19; // Assign

data[1] = 40;

data[2] = 75;

data[3] = 76;

data[4] = 90;

int[] data = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 }; // Declare, create, assign

Read Array Elements

After an array is defined and assigned values, its data can be accessed and used within the code. An array element is accessed with the name of the array variable, followed by brackets around the element position to read.

int[] data = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 };

line(data[0], 0, data[0], 100);

line(data[1], 0, data[1], 100);

line(data[2], 0, data[2], 100);

line(data[3], 0, data[3], 100);

line(data[4], 0, data[4], 100);

Remember, the first element in the array is in the 0 position. If you try to access a member of the array that lies outside the array boundaries, your program will terminate and give an ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException.

int[] data = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 };

println(data[0]); // Prints "19" to the console

println(data[2]); // Prints "75" to the console

println(data[5]); // ERROR! The last element of the array is 4

The length field stores the number of elements in an array. This field is stored within the array and is accessed with the dot operator. The following example demonstrates how to utilize it.

int[] data1 = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 };

int[] data2 = { 19, 40 };

int[] data3 = new int[127];

println(data1.length); // Prints "5" to the console

println(data2.length); // Prints "2" to the console

println(data3.length); // Prints "127" to the console

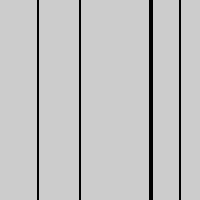

Usually, a for loop is used to access array elements, especially with large arrays. The following example draws the same lines as the previous code but uses a for loop to iterate through every value in the array.

int[] data = { 19, 40, 75, 76, 90 };

for (int i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

line(data[i], 0, data[i], 100);

}

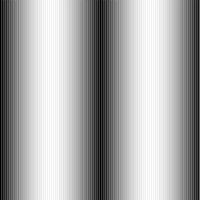

A for loop can also be used to put data inside an array. For instance, it can calculate a series of numbers and then assign each value to an array element. The following example stores the values from the sin() function in an array within setup() and then displays these values as the stroke values for lines within draw().

float[] sineWave;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

sineWave = new float[width];

for (int i = 0; i < sineWave.length; i++) {

// Fill array with values from sin()

float r = map(i, 0, width, 0, TWO_PI);

sineWave[i] = abs(sin(r));

}

}

void draw() {

for (int i = 0; i < sineWave.length; i++) {

// Set stroke values to numbers read from array

stroke(sineWave[i] * 255);

line(i, 0, i, height);

}

}

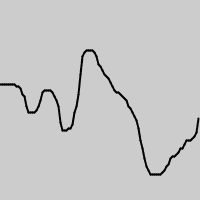

Record Data

As one example of how arrays may be used, this section shows how to use arrays to store data from the mouse. The pmouseX and pmouseY variables store the cursor coordinates from the previous frame, but there is no built-in way to access the cursor values from earlier frames. At every frame, the mouseX, mouseY, pmouseX, and pmouseY variables are replaced with new numbers and their previous numbers are discarded. Creating an array is the easiest way to store the history of these values. In the following example, the most recent 100 values from mouseY are stored and displayed on screen as a line from the left to the right edge of the screen. At each frame, the values in the array are shifted to the right and the newest value is added to the beginning.

int[] y;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

y = new int[width];

}

void draw() {

background(204); // Read the array from the end to the

// beginning to avoid overwriting the data

for (int i = y.length-1; i > 0; i--) {

y[i] = y[i-1];

}

// Add new values to the beginning

y[0] = mouseY;

// Display each pair of values as a line

for (int i = 1; i < y.length; i++) {

line(i, y[i], i-1, y[i-1]);

}

}

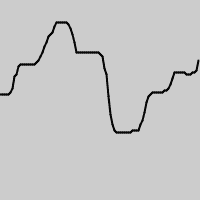

Apply the same code simultaneously to the mouseX and mouseY values to store the position of the cursor. Displaying these values each frame creates a trail behind the cursor.

int num = 50;

int[] x = new int[num];

int[] y = new int[num];

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

noStroke();

fill(255, 102);

}

void draw() {

background(0);

// Shift the values to the right

for (int i = num-1; i > 0; i--) {

x[i] = x[i-1];

y[i] = y[i-1];

}

// Add the new values to the beginning of the array

x[0] = mouseX;

y[0] = mouseY;

// Draw the circles

for (int i = 0; i < num; i++) {

ellipse(x[i], y[i], i/2.0, i/2.0);

}

}

The following example produces the same result as the previous one but uses a more efficient technique. Instead of shifting the array elements in each frame, the program writes the new data to the next available array position. The elements in the array remain in the same position once they are written, but they are read in a different order each frame. Reading begins at the location of the oldest data element and continues to the end of the array. At the end of the array, the % operator (p. 57) is used to wrap back to the beginning. This technique, commonly known as a ring buffer, is especially useful with larger arrays, to avoid unnecessary copying of data that can slow down a program.

int num = 50;

int[] x = new int[num];

int[] y = new int[num];

int indexPosition = 0;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

noStroke();

fill(255, 102);

}

void draw() {

background(0);

x[indexPosition] = mouseX;

y[indexPosition] = mouseY;

// Cycle between 0 and the number of elements

indexPosition = (indexPosition + 1) % num;

for (int i = 0; i < num; i++) {

// Set the array position to read

int pos = (indexPosition + i) % num;

float radius = (num-i) / 2.0;

ellipse(x[pos], y[pos], radius, radius);

}

}

Array Functions

Processing provides a group of functions that assist in managing array data. Only four of these functions are introduced here, but more are explained in the Processing reference included with the software.

The append() function expands an array by one element, adds data to the new position, and returns the new array:

String[] trees = { "ash", "oak" };

append(trees, "maple"); // INCORRECT! Does not change the array

printArray(trees); // Prints [0] "ash", [1] "oak"

println();

trees = append(trees, "maple"); // Add "maple" to the end

printArray(trees); // Prints [0] "ash", [1] "oak", [2] "maple"

println();

// Add "beech" to the end of the trees array, and creates a new

// array to store the change

String[] moretrees = append(trees, "beech");

// Prints [0] "ash", [1] "oak", [2] "maple", [3] "beech"

printArray(moretrees);

The shorten() function decreases an array by one element by removing the last element and returns the shortened array:

String[] trees = { "lychee", "coconut", "fig" };

trees = shorten(trees); // Remove the last element from the array

printArray(trees); // Prints [0] "lychee", [1] "coconut"

println();

trees = shorten(trees); // Remove the last element from the array

printArray(trees); // Prints [0] "lychee"

The expand() function increases the size of an array. It can expand to a specific size, or if no size is specified, the array's length will be doubled. If an array needs to have many additional elements, it's faster to use expand() to double the size than to use append() to continually add one value at a time. The following example saves a new mouseX value to an array every frame. When the array becomes full, the size of the array is doubled and new mouseX values proceed to fill the enlarged array.

int[] x = new int[100]; // Array to store x-coordinates

int count = 0; // Positions stored in array

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

}

void draw() {

x[count] = mouseX; // Assign new x-coordinate to the array

count++; // Increment the counter

if (count == x.length) { // If the x array is full,

x = expand(x); // double the size of x

println(x.length); // Write the new size to the console

}

}

Array values cannot be copied with the assignment operator because they are objects. The most common way to copy elements from one array to another is to use special functions or to copy each element individually within a for loop. The arrayCopy() function is the most efficient way to copy the entire contents of one array to another. The data is copied from the array used as the first parameter to the array used as the second parameter. Both arrays must be the same length for it to work in the configuration shown here.

String[] north = { "OH", "IN", "MI" };

String[] south = { "GA", "FL", "NC" };

arrayCopy(north, south); // Copy from north array to south array

printArray(south); // Prints [0] "OH", [1] "IN", [3] "MI"

println();

String[] east = { "MA", "NY", "RI" };

String[] west = new String[east.length]; // Create a new array

arrayCopy(east, west); // Copy from east array to west array

printArray(west); // Prints [0] "MA", [1] "NY", [2] "RI"

New functions can be written to perform operations on arrays, but arrays behave differently than data types such as int and char. As with objects, when an array is used as a parameter to a function, the address (location in memory) of the array is transferred into the function instead of the actual data. No new array is created, and changes made within the function affect the array used as the parameter.

In the following example, the data[] array is used as the parameter to halve(). The address of data[] is passed to the d[] array in the halve() function. Because the address of d[] and data[] is the same, they both point to the same data. Changes made to d[] on line 14 modify the value of data[] in the setup() block. The draw() function is not used because the calculation is made only once and nothing is drawn to the display window.

float[] data = { 19.0, 40.0, 75.0, 76.0, 90.0 };

void setup() {

halve(data);

println(data[0]); // Prints "9.5"

println(data[1]); // Prints "20.0"

println(data[2]); // Prints "37.5"

println(data[3]); // Prints "38.0"

println(data[4]); // Prints "45.0"

}

void halve(float[] d) {

for (int i = 0; i < d.length; i++) { // For each array element,

d[i] = d[i] / 2.0; // divide the value by 2

}

}

Changing array data within a function without modifying the original array requires some additional lines of code. In the following example, the array is passed into the function as a parameter, a new array is made, the values from the original array are copied in the new array, changes are made to the new array, and finally the modified array is returned.

float[] data = { 19.0, 40.0, 75.0, 76.0, 90.0 };

float[] halfData;

void setup() {

halfData = halve(data); // Run the halve() function

println(data[0], halfData[0]); // Prints "19.0, 9.5"

println(data[1], halfData[1]); // Prints "40.0, 20.0"

println(data[2], halfData[2]); // Prints "75.0, 37.5"

println(data[3], halfData[3]); // Prints "76.0, 38.0"

println(data[4], halfData[4]); // Prints "90.0, 45.0"

}

float[] halve(float[] d) {

float[] numbers = new float[d.length]; // Create a new array

arrayCopy(d, numbers);

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) { // For each element,

numbers[i] = numbers[i] / 2.0; // divide the value by 2

}

return numbers; // Return the new array

}

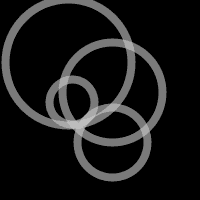

Array of Objects

Working with arrays of objects is technically similar to working with arrays of other data types, but it opens the amazing possibility to create as many instances of a custom-designed class as desired. Like all arrays, an array of objects is distinguished from a single object with brackets, the [ and ] characters. However, because each array element is an object, each must be created with the keyword new before it can be used. The steps for working with an array of objects are:

Declare the array

Create the array

Create each object in the array

These steps are translated into code in the following example. It uses the Ring class from page 371, so copy it over or retype it. This code creates a rings[] array to hold fifty Ring objects. Space in memory for the rings[] array is allocated in setup() and each Ring object is created. The first time a mouse button is pressed, the first Ring object is turned on and its x and y variables are assigned to the current values of the cursor. Each time a mouse button is pressed, a new Ring is turned on and displayed in the subsequent trip through draw(). When the final element in the array has been created, the program jumps back to the beginning of the array to assign new positions to earlier Rings.

Ring[] rings; // Declare the array

int numRings = 50;

int currentRing = 0;

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

rings = new Ring[numRings]; // Create the array

for (int i = 0; i < rings.length; i++) {

rings[i] = new Ring(); // Create each object

}

}

void draw() {

background(0);

for (int i = 0; i < rings.length; i++) {

rings[i].grow();

rings[i].display();

}

}

// Click to create a new Ring

void mousePressed() {

rings[currentRing].start(mouseX, mouseY);

currentRing++;

if (currentRing >= numRings) {

currentRing = 0;

}

}

class Ring {

float x, y; // X-coordinate, y-coordinate

float diameter; // Diameter of the ring

boolean on = false; // Turns the display on and off

void start(float xpos, float ypos) {

x = xpos;

y = ypos;

diameter = 1;

on = true;

}

void grow() {

if (on == true) {

diameter += 0.5;

if (diameter > 400) {

on = false;

diameter = 1;

}

}

}

void display() {

if (on == true) {

noFill();

strokeWeight(4);

stroke(204, 153);

ellipse(x, y, diameter, diameter);

}

}

}

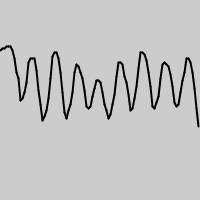

The next example requires the Spot class from page 363. Unlike the prior example, variable values are generated within the setup() and are passed into each array elements through the object's constructor. Each element in the array starts with a unique set of x-coordinate, diameter, and speed values. Because the number of objects is dependent on the width of the display window, it is not possible to create the array until the program knows how wide it will be. Therefore, the array is declared outside of setup() to make it global (see p. 12), but it is created inside setup, after the width of the display window is defined.

Spot[] spots; // Declare array

void setup() {

size(700, 100);

int numSpots = 70; // Number of objects

int dia = width/numSpots; // Calculate diameter

spots = new Spot[numSpots]; // Create array

for (int i = 0; i < spots.length; i++) {

float x = dia/2 + i*dia;

float rate = random(0.1, 2.0);

// Create each object

spots[i] = new Spot(x, 50, dia, rate);

}

noStroke();

}

void draw() {

fill(0, 12);

rect(0, 0, width, height);

fill(255);

for (int i=0; i < spots.length; i++) {

spots[i].move(); // Move each object

spots[i].display(); // Display each object

}

}

class Spot {

float x, y; // X-coordinate, y-coordinate

float diameter; // Diameter of the circle

float speed; // Distance moved each frame

int direction = 1; // Direction of motion (1 is down, -1 is up)

// Constructor

Spot(float xpos, float ypos, float dia, float sp) {

x = xpos;

y = ypos;

diameter = dia;

speed = sp;

}

void move() {

y += (speed * direction);

if ((y > (height - diameter/2)) || (y < diameter/2)) {

direction *= -1;

}

}

void display() {

ellipse(x, y, diameter, diameter);

}

}

Working with arrays of objects gives us the opportunity to access each object with a code structure called an enhanced for loop to simplify the code. Unlike the for loop used previously in this chapter, the enhanced loop automatically goes through each element in an array one by one without needing to define the start and stop conditions. An enhanced loop is structured by stating the data type of the array elements, a variable name to assign to each element of the array, and the name of the array. For instance, the for loop in code 28-25 is rewritten like this:

for (Spot s : spots) {

s.move();

s.display();

}

Each object in the array is in turn assigned to the variable s, so the first time through the loop, the code s.move() runs the move() method for the first element in the array, then the next time through the loop, s.move() runs the move() method for the second element in the array, etc. The two statements inside the block run for each element of the array until the end of the array. This way of accessing each element in an array of objects is used for the remainder of the book.

Two-dimensional Arrays

Data can also be stored and retrieved from arrays with more than one dimension. Using the example from the beginning of this chapter, the data points for the chart are put into a 2D array, where the second dimension adds a gray value:

A 2D array is essentially a list of 1D arrays. It must first be declared, then created, and then the values can be assigned just as in a 1D array. The following syntax converts the diagram above into to code:

int[][] x = { {50, 0}, {61,204}, {83,51}, {69,102}, {71, 0},

{50,153}, {29, 0}, {31,51}, {17,102}, {39,204} };

println(x[0][0]); // Prints "50"

println(x[0][1]); // Prints "0"

println(x[4][2]); // ERROR! This element is outside the array

println(x[3][0]); // Prints "69"

println(x[9][1]); // Prints "204"

This sketch shows how it all fits together.

int[][] x = { {50, 0}, {61,204}, {83,51}, {69,102},

{71, 0}, {50,153}, {29, 0}, {31,51},

{17,102}, {39,204} };

void setup() {

size(100, 100);

}

void draw() {

for (int i = 0; i < x.length; i++) {

fill(x[i][1]);

rect(0, i*10, x[i][0], 8);

}

}

It is possible to continue and make 3D and 4D arrays by extrapolating these techniques. However, multidimensional arrays can be confusing, and often it is a better idea to maintain multiple 1D or 2D arrays.